Writing Interferes with Learning

If you go into any traditional English however, you see the teacher writing out sentences on their whiteboards, referring students to textbooks and giving them written handouts and written assignments. You’ll see the students studiously writing notes, doing written assignments, doing various practice exercises in student books and taking written tests.

The time we spend engaged in speaking and listening in the real world does not match the time we devote to these skills in the classroom. And this is reflected in the students ability to understand and speak English. They know the grammar inside and out, but they can’t understand what English speakers are saying. They can read easily, but as soon as they need to communicate with someone they struggle to both understand and speak.

The time we spend engaged in speaking and listening in the real world does not match the time we devote to these skills in the classroom. And this is reflected in the students ability to understand and speak English. They know the grammar inside and out, but they can’t understand what English speakers are saying. They can read easily, but as soon as they need to communicate with someone they struggle to both understand and speak.

I would argue that not only is this emphasis on the written word ineffective in teaching students to communicate, it actually stops them from learning to communicate, especially in the beginner and early intermediate levels of instruction.

As native English speakers we think that written English is simply a translation of spoken English to paper (or screen). We see words on a page and think that’s what we say. In fact, written and spoken English are two entirely different languages. Native speakers are so familiar with both forms that we map one onto the other in our minds when no real direct mapping exists.

Don’t believe me? Let’s go down the rabbit hole and take a closer look.

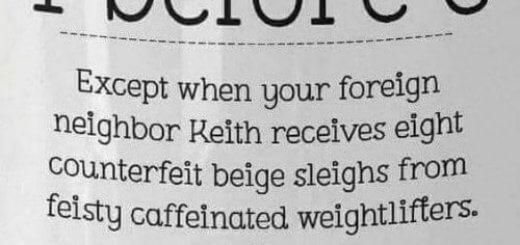

First of all, we don’t separate words where spaces appear. When you say this sentence you think that you say each word: “I want a bit of egg.” When in fact, if you could turn off your filter and listen to what’s actually said you’d hear: “I wa nuh bi tuh vegg.”

You may have also noticed in that sentence that we changed the sounds that we think were represented by the letters. Why do we have d’s in the middle of the word “little” (liddl)? Why do you start the word “Tuesday” with a ch sound (chews-day)? Why do you pronounce two a’s in the word “banana” as uh sounds (buh-na-nuh)?

We add sounds where they don’t exist. Just say the conjugation of “to be” out loud and listen to yourself: I yam, you ware, he yis. When I tell people they do wit all the time, they say, “No, wI don’t!”

And conversely we drop out sounds where they should exist. We say to our dogs, “Who’s a guh boy?” and if we don’t like cream we tell people about our preference for “bla coffee”. You may wanna argue with me, but if you say these words out loud you know I’m right. Hey! Where did the t’s in “want to argue” go.

The bottom line is that what students hear is entirely different from what they read. Using the written word to teach spoken English is simply confusing and stops them from learning.